Introduction

Higher vertebrates, including humans, have evolved a highly specialized defense system to protect themselves against invading foreign substances such as viruses, bacteria, parasites, and foreign proteins.

The collective defense strategies of the body are known as Immunity.

Immunology is the branch of science that deals with the study of defense mechanisms by which the body recognizes self from non-self and eliminates foreign substances.

Basic Terminology

-

Antigen / Immunogen: A substance that induces an immunological response

-

Antibody: Glycoprotein molecules produced by plasma cells in response to antigens

-

All antibodies are immunoglobulins

-

Immunoglobulins belong mainly to the gamma-globulin fraction of plasma proteins (on electrophoresis)

-

Immunoglobulin is a functional term, whereas gamma-globulin is a physical term

Types of Immunity

Immune defenses operate through two interdependent mechanisms:

1. Innate Immunity (Natural / Non-specific Immunity)

Innate immunity is the first line of defense present from birth. It does not recognize specific antigens and responds in the same manner to all foreign invaders.

Characteristics

-

Present at birth

-

Non-specific response

-

No immunological memory

-

Immediate response

Components of Innate Immunity

-

Physical barriers: Skin, mucous membranes

-

Chemical barriers: Gastric acid, lysozyme, sweat

-

Cellular defenses: Neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells

-

Inflammation

-

Complement system

-

Interferons

-

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)

Functions

-

Prevents entry of pathogens

-

Limits spread of infection

-

Activates adaptive immunity

2. Adaptive Immunity (Acquired / Specific Immunity)

Adaptive immunity develops after exposure to specific antigens. It is highly specific and provides long-lasting protection due to immunological memory.

Characteristics

-

Develops after birth

-

Antigen-specific

-

Has memory

-

Stronger and more effective response upon re-exposure

Adaptive immunity is mediated by lymphocytes and is divided into two main types:

A. Humoral Immunity

-

Mediated by B-lymphocytes

-

Involves production of antibodies (immunoglobulins)

-

Effective against extracellular pathogens such as bacteria and toxins

Major Features

-

Antibodies circulate in blood and body fluids

-

Neutralization of toxins

-

Activation of complement system

-

Opsonization of pathogens

B. Cell-Mediated Immunity

-

Mediated by T-lymphocytes

-

Does not involve antibodies

-

Effective against intracellular pathogens, viruses, fungi, and tumor cells

Major Functions

-

Killing virus-infected cells

-

Activation of macrophages

-

Rejection of transplanted tissues

-

Delayed type hypersensitivity reactions

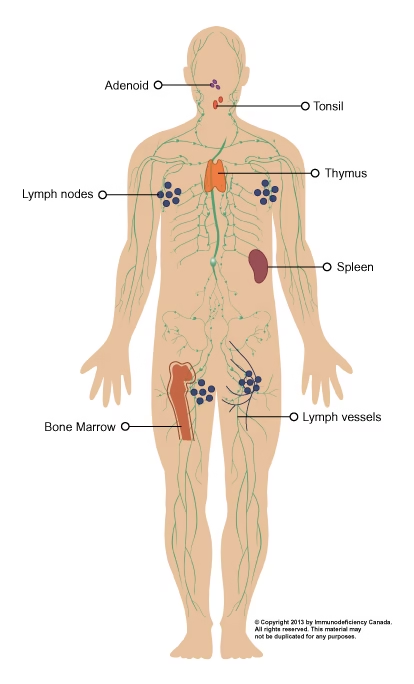

Organization of the Immune System

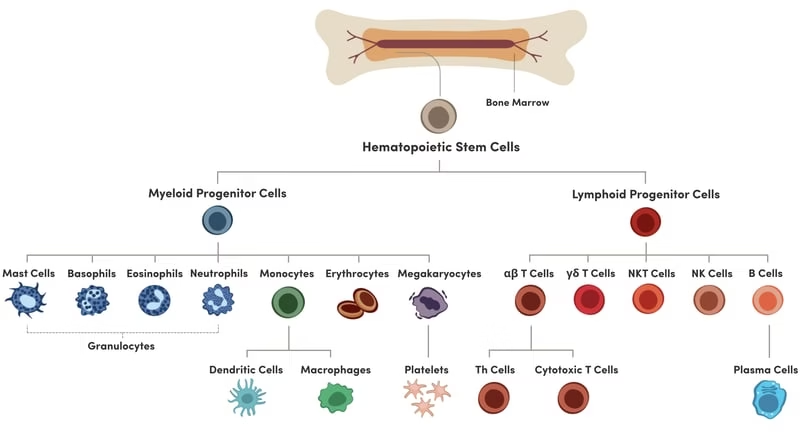

Cells Involved in Immune Responses

B-Lymphocytes

-

Specifically recognize antigens

-

Produce antibodies (immunoglobulins)

-

Responsible for humoral immunity

T-Lymphocytes

-

Recognize antigens presented on cell surfaces

-

Involved in cell-mediated immunity

-

Play a key role in viral and intracellular infections

Cytokines

-

Regulatory proteins

-

Control cell division (mitosis)

-

Mediate communication between immune cells

Innate Immunity (Non-Specific Immunity)

Innate immunity defends against foreign substances without recognizing specific identity.

Components of Innate Immunity

-

Defenses at body surfaces (skin, mucosa)

-

Inflammation

-

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)

-

Complement system

-

Interferons

Adaptive Immunity (Specific Immunity)

Adaptive immunity:

-

Responds mainly to macromolecules (proteins)

-

Produces antibodies against antigens

-

Mediated by lymphocytes

Types of Adaptive Immunity

-

Humoral Immunity – mediated by antibodies

-

Cell-Mediated Immunity – mediated by T-cells

Structure and Classes of Immunoglobulins

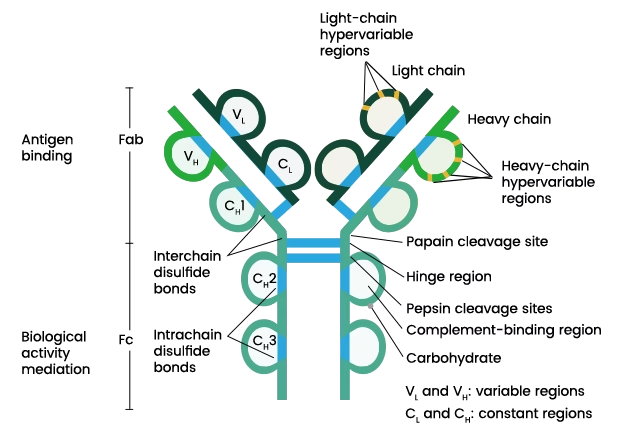

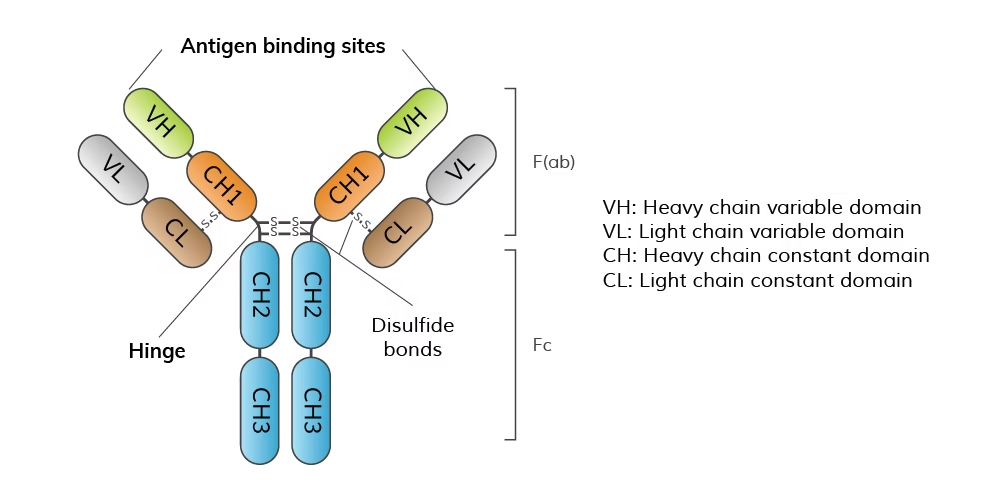

Structure of Immunoglobulins

Structure of Immunoglobulins

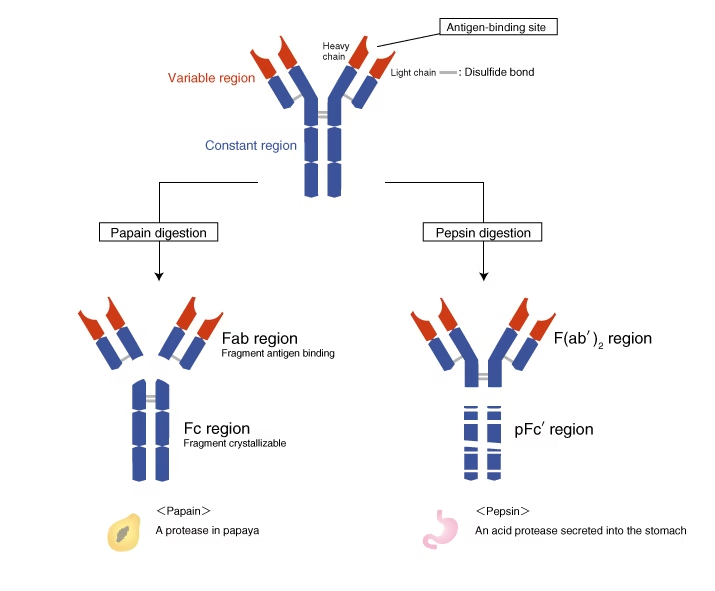

The basic structure of immunoglobulin was proposed by Rodney Porter and Gerald Edelman (1962).

Structural Features

-

Two identical Heavy (H) chains (MW 53,000–75,000)

-

Two identical Light (L) chains (MW ~23,000)

-

Chains linked by disulfide bonds

-

Y-shaped tetramer (H₂L₂)

-

Heavy chain: ~450 amino acids

-

Light chain: ~212 amino acids

Regions of Chains

Regions of Chains

-

Variable region (V) – antigen binding

-

Constant region (C) – biological function

Papain Digestion

-

Cleaves at hinge region

-

Produces:

-

2 Fab fragments (antigen binding)

-

1 Fc fragment (effector function)

-

Production of Immunoglobulins

-

Light chains are produced by 3 genes

-

Heavy chains are produced by 4 genes

-

Multiple genes contribute to antibody diversity

Classes of Immunoglobulins

Humans possess five classes of immunoglobulins, determined by the type of heavy chain.

| Class | Heavy Chain | Structural Form |

|---|---|---|

| IgG | γ (gamma) | Monomer |

| IgA | α (alpha) | Monomer / Dimer |

| IgM | μ (mu) | Pentamer |

| IgD | δ (delta) | Monomer |

| IgE | ε (epsilon) | Monomer |

Two light chains:

-

Kappa (κ) – more common

-

Lambda (λ)

(An Ig molecule contains either κ or λ, never both)

Individual Classes of Immunoglobulins

1. IgG (Immunoglobulin G)

-

Most abundant immunoglobulin (~75% of total serum Ig)

-

Major antibody in serum and extracellular fluids

-

Exists as a monomer

-

Only immunoglobulin that crosses the placenta, providing passive immunity to the fetus

-

Activates the complement system

-

Plays a central role in humoral immunity

Functions of IgG

-

Neutralization of toxins and viruses

-

Opsonization of pathogens

-

Complement-mediated cell lysis

-

Transfer of maternal immunity to fetus

2. IgA (Immunoglobulin A)

-

Present as monomer in blood and dimer in secretions

-

Dimeric IgA contains a J (joining) chain

-

Predominant immunoglobulin in body secretions

-

Saliva

-

Tears

-

Sweat

-

Colostrum

-

Breast milk

-

Bronchial and intestinal secretions

-

-

Known as secretory antibody

Functions of IgA

-

Protects mucosal surfaces

-

Prevents attachment and invasion of pathogens

-

Provides passive immunity to newborns via colostrum and breast milk

3. IgM (Immunoglobulin M)

-

Largest immunoglobulin

-

Exists as a pentamer linked by a J chain

-

Also known as macroglobulin

-

First antibody produced:

-

During primary immune response

-

By the fetus

-

-

Restricted to the bloodstream due to large size

-

Highly effective in activating the complement system

Functions of IgM

-

First line of defense in acute infections

-

Strong agglutinating activity

-

Effective elimination of invading microorganisms

4. IgD (Immunoglobulin D)

-

Present in very low concentration in serum

-

Exists as a monomer

-

Primarily found on the surface of B-lymphocytes

-

Functions as a B-cell receptor (BCR)

Functions of IgD

-

Regulation of B-cell activation and differentiation

-

Exact biological role is not fully understood

5. IgE (Immunoglobulin E)

-

Least abundant immunoglobulin in serum

-

Exists as a monomer

-

Binds strongly to mast cells and basophils

-

Levels are elevated in allergic conditions

Functions of IgE

-

Mediates Type I hypersensitivity reactions

-

Triggers release of histamine and other mediators

-

Responsible for allergic manifestations such as:

-

Asthma

-

Allergic rhinitis

-

Anaphylaxis

-

Structural Classification Summary

-

Monomeric Immunoglobulins:

IgG, IgD, IgE -

Polymeric Immunoglobulins:

IgA (Dimer), IgM (Pentamer)

Gammapathies and Paraproteinemia

Gammapathies

Gammapathies are disorders characterized by excessive production of immunoglobulins or their fragments, produced by a single clone or multiple clones of plasma cells. These abnormal immunoglobulins are usually detected in the gamma region during serum protein electrophoresis.

Gammapathies are broadly classified into:

-

Benign (Polyclonal) gammapathies

-

Malignant (Monoclonal) gammapathies

Malignant Gammapathies

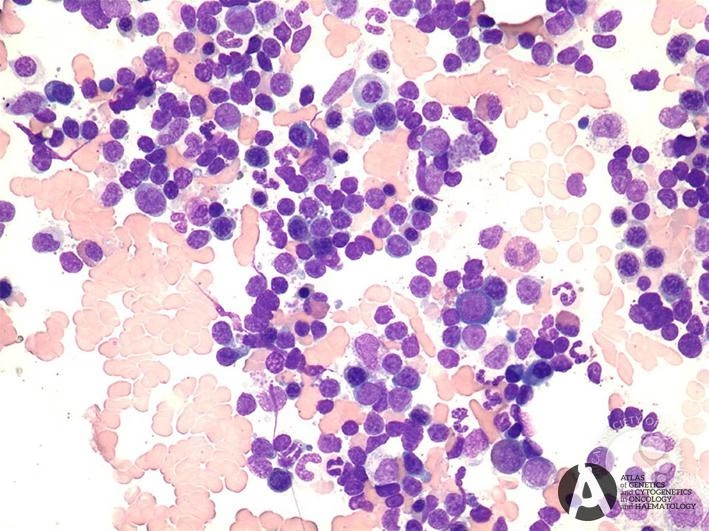

Multiple Myeloma (MM)

-

A malignant plasma cell disorder

-

Characterized by excessive production of a single type of immunoglobulin (monoclonal Ig)

-

Appears as a sharp M-band (monoclonal band) on serum protein electrophoresis

-

Malignant plasma cells produce large quantities of either:

-

Kappa (κ) light chains or

-

Lambda (λ) light chains

These monoclonal immunoglobulins are called paraproteins

-

Bence-Jones Myeloma (Light Chain Disease)

-

A special type of multiple myeloma

-

Plasma cells produce free light chains only

-

Light chains are excreted in urine as Bence-Jones proteins

-

Thermal property:

-

Precipitate at 45–60°C

-

Redissolve at 80°C

-

-

These proteins can block renal tubules, leading to renal failure

Paraproteinemia

Paraproteinemia refers to the presence of abnormal monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments in the blood due to clonal proliferation of plasma cells.

Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia

-

Characterized by excessive production of IgM

-

Commonly seen in elderly males

-

Caused by malignant proliferation of IgM-producing plasma cell clones

-

High IgM levels cause:

-

Increased serum viscosity

-

Recurrent bleeding

-

Visual disturbances

-

Neurological symptoms

-

Benign (Polyclonal) Gammapathies

Hypergammaglobulinemia

-

Increase in multiple immunoglobulin classes

-

Occurs due to chronic antigenic stimulation

-

Commonly seen in:

-

Tuberculosis

-

Malaria

-

Chronic infections

-

-

Represents a reactive, non-malignant condition

Table: Gammapathies and Paraproteinemia

| Condition | Type of Ig | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Myeloma | IgG / IgA | M-band on electrophoresis |

| Bence-Jones Myeloma | κ or λ light chains | Proteinuria, renal damage |

| Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia | IgM | Increased serum viscosity |

| Hypergammaglobulinemia | Polyclonal Ig | Chronic infections |

Clinical Importance

-

Detection is commonly done by serum protein electrophoresis

-

Urine examination is essential for Bence-Jones proteins

-

These disorders are important causes of:

-

Anemia

-

Renal failure

-

Bone lesions

-

Recurrent infections

-

Disorders of the Immune System

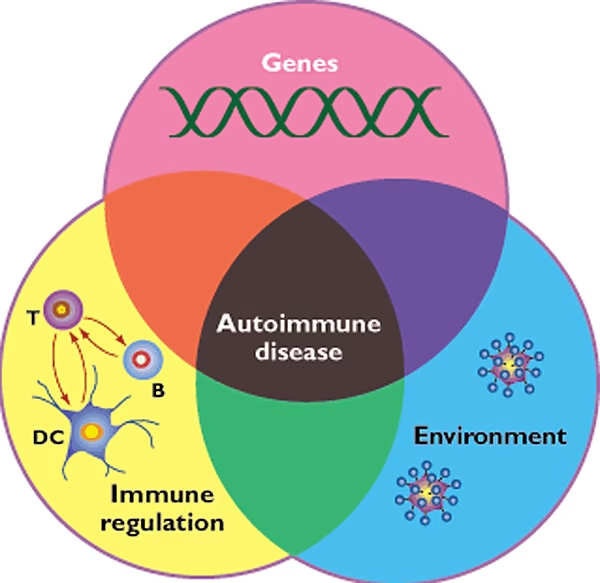

Autoimmune Diseases

-

Failure to distinguish self from non-self

-

Escape of autoreactive T and B cells

-

Leads to tissue inflammation and damage

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions are classified into four types (Type I–IV) based on:

- Immune mechanism involved

- Type of immune effector

- Time taken for reaction

Type I Hypersensitivity

Mechanism

- Mediated by IgE antibodies

- First exposure → sensitization

- IgE binds to mast cells and basophils

- Re-exposure → antigen cross-links IgE → histamine release

Common Allergens

- Pollens

- Foods (milk, eggs, nuts)

- House dust, mites, ticks

- Animal dander

- Drugs

Clinical Manifestations

- Allergic rhinitis

- Bronchial asthma

- Urticaria

- Anaphylaxis (severe systemic reaction)

Type II Hypersensitivity (Cytotoxic Reaction)

Mechanism

- Mediated by IgG or IgM antibodies

- Antibodies react with cell surface antigens

- Leads to:

- Complement-mediated cell lysis

- Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

Examples

- Blood transfusion reactions (ABO incompatibility)

- Hemolytic disease of the newborn (Rh incompatibility)

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Type III Hypersensitivity (Immune Complex Reaction)

Mechanism

- Formation of antigen–antibody immune complexes

- Deposition in tissues such as:

- Kidneys

- Joints

- Blood vessels

- Activation of complement → inflammation

Examples

- Glomerulonephritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Serum sickness

Type IV Hypersensitivity

Mechanism

- Cell-mediated immunity

- Mediated by CD4⁺ T-helper (TDTH) cells

- No antibody involvement

- Cytokine release → macrophage activation

Key Features

- Reaction appears 24–48 hours after exposure

- Inflammatory response is delayed

Examples

- Contact dermatitis

- Tuberculin skin test

- Granulomatous inflammation

Immunodeficiency Diseases

Primary

-

Genetic defects

Secondary (Acquired)

-

AIDS caused by HIV infection

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

Mode of Transmission

-

Sexual contact (most common)

-

IV drug abuse

-

Blood transfusion

-

Vertical transmission

Immunology of AIDS

-

CD4 count falls below 400/cu.mm

-

Reduced antibody production

-

Decreased cytokines (IL-2, interferons)

Laboratory Diagnosis

-

ELISA – screening test

-

Western blot – confirmatory test

-

HIV antigen detection

-

RT-PCR for HIV RNA

Vaccine Development and Immunization

Immunization

Immunization is the process by which artificial immunity (resistance to a specific infectious disease) is developed in an individual by the administration of immunizing agents.

It is one of the most effective and economical public health interventions for disease prevention.

Importance of Immunization

-

Protects children against major infectious diseases through routine immunization

-

Forms an integral part of the basic health care system

-

Increases herd immunity, thereby controlling the spread of infections

-

Provides protection to high-risk individuals and groups

-

Reduces morbidity, mortality, and disease-related complications

Immunizing Agents

Immunizing agents used to induce immunity are classified into:

-

Vaccines

-

Immunoglobulins

-

Antisera / Antitoxins

Vaccines

A vaccine is a biological preparation derived from microorganisms or other biological substances (such as toxins or allergens) that stimulates the immune system to develop active immunity against a specific disease.

Vaccines may be prepared from:

-

Live organisms

-

Killed organisms

-

Bacterial toxins

-

Extracted cellular fractions

-

Recombinant antigens

Classification of Vaccines

Vaccines are classified into five major types based on their method of preparation.

1. Live Attenuated Vaccines

Definition

Live vaccines contain live microorganisms with reduced virulence, capable of inducing infection without causing disease.

Characteristics

-

Produce immunity similar to natural infection

-

Long-lasting immunity

-

Booster doses usually not required

Advantages

-

Single dose often sufficient

-

Can be administered via natural route of infection

-

Induce both humoral and cell-mediated immunity

-

Provide long-term protection

Disadvantages

-

Risk of reversion to virulence

-

Unsafe in immunocompromised individuals

-

May spread to contacts

2. Killed (Inactivated) Vaccines

Definition

Contain microorganisms that have been killed or inactivated using heat, phenol, or formalin.

Characteristics

-

Do not multiply in the host

-

Induce weaker immunity than live vaccines

-

Immunity is short-lived

Advantages

-

Safe and stable

-

No risk of disease transmission

-

Can be combined as polyvalent vaccines

Disadvantages

-

Multiple booster doses required

-

Cannot be given orally

-

Poor cell-mediated immunity

-

May cause local reactions

3. Toxoids

Certain bacteria (e.g., diphtheria and tetanus bacilli) produce exotoxins that cause disease. These toxins can be detoxified to form toxoids, which are non-toxic but antigenic.

Key Points

-

Prepared using formalin or heat

-

Induce production of antitoxins

-

Used for active immunization

Examples

-

Tetanus toxoid (TT)

-

Diphtheria toxoid (DT)

Potentiation

-

Antigenicity enhanced by adjuvants

-

Combined with other vaccines (e.g., DPT)

4. Cellular Fraction and Subunit Vaccines

Cellular Fraction Vaccines

Prepared from extracted components of microorganisms.

Examples:

-

Meningococcal vaccine (cell wall antigen)

-

Pneumococcal vaccine (capsular polysaccharide)

-

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine

Subunit Vaccines

-

Only immunogenic components are used

-

Prepared using chemical or detergent methods

Examples:

-

Rabies vaccine

-

Influenza vaccine

5. Recombinant Vaccines

Definition

Produced using recombinant DNA technology, where genes encoding immunogenic antigens are cloned into suitable vectors.

Advantages

-

Safe and highly specific

-

Large-scale production possible

Examples

-

Hepatitis B vaccine

-

Influenza vaccine

6. Combined (Mixed) Vaccines

Vaccines containing more than one immunizing agent.

Examples

-

DPT (Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus)

-

DT (Diphtheria, Tetanus)

-

DP (Diphtheria, Pertussis)

-

MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella)

-

DPTP (DPT + Polio)

Advantages

-

Fewer injections

-

Reduced hospital visits

-

Cost-effective

-

Improved compliance

Passive Immunization (Immunotherapy)

Passive immunization involves administration of preformed antibodies to provide immediate but temporary protection.

Immunoglobulins

1. Normal Human Immunoglobulin

-

Prepared from pooled plasma of ≥1000 donors

-

Rich in IgG

Uses

-

Prevention of measles

-

Protection against hepatitis A

-

Temporary immunity in high-risk individuals

2. Specific Human Immunoglobulin

Prepared from:

-

Convalescent individuals

-

Hyper-immunized donors

Examples

-

Rabies immunoglobulin

-

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin

-

Tetanus immunoglobulin

Antisera and Antitoxins

-

Prepared in animals (horse, sheep, goat, rabbit)

-

Used only when no alternative is available

Examples

-

Anti-tetanus serum (ATS)

-

Anti-diphtheria serum (ADS)

-

Anti-snake venom (ASV)

Limitations

-

Short half-life

-

Risk of hypersensitivity reactions

-

Serum sickness and anaphylaxis

Active vs Passive Immunization

| Feature | Active | Passive |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody source | Host | External |

| Onset | Slow | Immediate |

| Duration | Long | Short |

| Memory | Present | Absent |